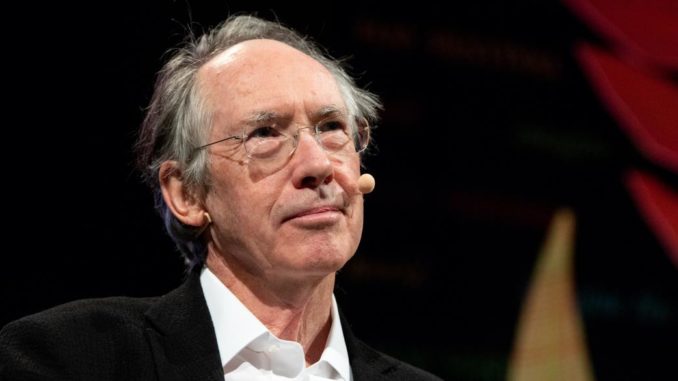

Ian McEwan at Dickinson College (2015)

My most sincere congratulations to all the graduates here. You made it through. You have a degree from a truly excellent institution. A lot of reading, writing, lying in bed (thinking, of course). And now you stand on one of life’s various summits. As you know, there’s only one way off a summit – but that’s another story. Don’t be taken in by those who tell you that life is short. It’s inordinately long. I was into my twenties when my mother astonished me by saying wistfully, ‘I’d give anything to be forty-five again.’ Forty-five sounded like old age to me then. Now I see what she meant. Most of you have more than 20 years before you peak. Barring all-out nuclear war or a catastrophic meteor collision, a substantial minority of you will get a toe in the door of the next century – a very wrinkled, arthritic toe, but the same toe you’re wearing now. You have a lot of years in the bank – but don’t worry, I’m not here to tell you how to spend them.

Instead, I would like to share a few thoughts with you about free speech (and speech here includes writing and reading, listening and thinking) – free speech – the life blood, the essential condition of the liberal education you’ve just received. Let’s begin on a positive note: there is likely more free speech, free thought, free enquiry on earth now than at any previous moment in recorded history (even taking into account the golden age of the so-called ‘pagan’ philosophers). And you’ve come of age in a country where the enshrinement of free speech in the First Amendment is not an empty phrase, as it is in many constitutions, but a living reality.

But free speech was, it is and always will be, under attack – from the political right, the left, the centre. It will come from under your feet, from the extremes of religion as well as from unreligious ideologies. It’s never convenient, especially for entrenched power, to have a lot of free speech flying around.

The words associated with Voltaire (more likely, his sentiments but not his actual phrasing) remain crucial and should never be forgotten: I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it. It’s only rarely appropriate to suppress the speech of those you disagree with. As my late friend Christopher Hitchens used to say, when you meet a flat-earther or a creationist, it can be useful to be made to remember just why you think the earth is round or whether you’re capable of making the case for natural selection. For that reason, it’s a poor principle, adopted in some civilised countries, to imprison the deniers of the Holocaust or the Armenian massacres, however contemptible they might be.

It’s worth remembering this: freedom of expression sustains all the other freedoms we enjoy. Without free speech, democracy is a sham. Every freedom we possess or wish to possess (of habeas corpus and due process, of universal franchise and of assembly, union representation, sexual equality, of sexual preference, of the rights of children, of animals – the list goes on) has had to be freely thought and talked and written into existence. No single individual can generate these rights alone. The process is cumulative. It was a historical context of relative freedom of speech that made possible the work of those who were determined to extend that liberty. John Milton, Tom Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill, Oliver Wendell Holmes – the roll call is long and honourable – and that is why an education in the liberal arts is so vital to the culture you are about to contribute to.

Take a long journey from these shores as I’m sure many of you will, and you will find the condition of free expression to be desperate. Across almost the entire Middle East, free thought can bring punishment or death, from governments or from street mobs or motivated individuals. The same is true in Bangladesh, Pakistan, across great swathes of Africa. These past years the public space for free thought in Russia has been shrinking. In China, state monitoring of free expression is on an industrial scale. To censor daily the internet alone, the Chinese government employs as many as fifty thousand bureaucrats – a level of thought repression unprecedented in human history.

Paradoxically, it’s all the more important to be vigilant for free expression wherever it flourishes. And nowhere has it been more jealously guarded than under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Which is why it has been so puzzling lately, when we saw scores of American writers publicly disassociating themselves from a PEN gala to honour the murdered journalists of the French satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo. American PEN exists to defend and promote free speech. What a disappointment that so many American authors could not stand with courageous fellow writers and artists at a time of tragedy. The magazine has been scathing about racism. It’s also scathing about organised religion and politicians and it might not be to your taste – but that’s when you should remember your Voltaire.

Hebdo’s offices were fire-bombed in 2011, and the journalists kept going. They received constant death threats – and they kept going. In January nine colleagues were murdered, gunned down, in their office – the editorial staff kept going and within days they had produced an edition whose cover forgave their attackers. Tout est pardonne, all is forgiven. All this, when in the U.S. and U.K. one threatening phone call can be enough to stop a major publishing house in its tracks.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo came from religious fanatics whose allegiances became clear when one of the accomplices made her way from France, through Turkey to ISIS in Syria. Remember, this is a form of fanaticism whose victims, across Africa and the Middle East, are mostly Muslims – Muslim gays and feminists, Muslim reformists, bloggers, human rights activists, dissidents, apostates, novelists, and ordinary citizens, including children, murdered in or kidnapped from their schools.

There’s a phenomenon in intellectual life that I call bi-polar thinking. Let’s not side with Charlie Hebdo because it might seem as if we’re endorsing George Bush’s ‘war on terror’. This is a suffocating form of intellectual tribalism and a poor way of thinking for yourself. As a German novelist friend wrote to me in anguish about the PEN affair -“It’s the Seventies again: Let’s not support the Russian dissidents, because it would get “applause from the wrong side.” That terrible phrase.”

But note the end of the Hebdo affair: the gala went ahead, the surviving journalists received a thunderous and prolonged standing ovation from American PEN.

Timothy Garton Ash reminds us in a new book on free speech that “The U.S. Supreme Court has described academic freedom as a ‘special concern of the First Amendment.’” Worrying too, then, is the case of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, an ex Muslim, highly critical of Islam, too critical for some. As a victim herself, she has campaigned against female genital mutilation. She has campaigned for the rights of Muslim women. In a recent book she has argued that for Islam to live more at ease in the modern world it needs to rethink its attitudes to homosexuality, to the interpretation of the Koran as the literal word of God, to blasphemy, to punishing severely those who want to leave the religion. Contrary to what some have suggested, such arguments are neither racist nor driven by hatred. But she has received death threats. Crucially, on many American campuses she is not welcomed, and, notoriously, Brandeis withdrew its offer of an honorary degree. Islam is worthy of respect, as indeed is atheism. We want respect flowing in all directions. But religion and atheism, and all thought systems, all grand claims to truth, must be open to criticism, satire, even, sometimes, mockery. Surely, we have not forgotten the lessons of the Salman Rushdie affair.

Campus intolerance of inconvenient speakers is hardly new. Back in the sixties my own university blocked a psychologist for promoting the idea of a hereditable component to intelligence. In the seventies, the great American biologist EO Wilson was drowned out for suggesting a genetic element in human social behaviour. As I remember, both men were called fascists. The ideas of these men did not fit prevailing ideologies, but their views are unexceptionable today.

More broadly – the internet has, of course, provided extraordinary possibilities for free speech. At the same time, it has taken us onto some difficult and unexpected terrain. It has led to the slow decline of local newspapers, and so removed a sceptical and knowledgeable voice from local politics. Privacy is an essential element of free expression; the Snowden files have revealed an extraordinary and unnecessary level of email surveillance by government agencies. Another essential element of free expression is access to information; the internet has concentrated huge power over that access into the hands of private companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter. We need to be careful that such power is not abused. Large pharmaceutical companies have been know to withhold research information vital to the public interest. On another scale, the death of young black men in police custody could be framed as the ultimate sanction against free expression. As indeed is poverty and poor educational resources.

All these issues need the input of men and women with a liberal arts education and you, graduates, are well placed to form your own conclusions. And you may reasonably conclude that free speech is not simple. It’s never an absolute. We don’t give space to proselytising paedophiles, to racists (and remember, race is not identical to religion) or to those who wish to incite violence against others. Wendell Holmes’s hypothetical ‘shouting fire in a crowded theatre’ is still relevant. But it can be a little too easy sometimes to dismiss arguments you don’t like as ‘hate speech’ or to complain that this or that speaker makes you feel ‘disrespected.’ Being offended is not to be confused with a state of grace; it’s the occasional price we all pay for living in an open society. Being robust is no bad thing. Either engage, with arguments – not with banishments and certainly not with guns – or, as an American Muslim teacher said recently at Friday prayers, ignore the entire matter.

In making your mind up on these issues, I hope you’ll remember your time at Dickinson and the novels you may have read here. It would prompt you, I hope, in the direction of mental freedom. The novel as a literary form was born out of the Enlightenment, out of curiosity about and respect for the individual. Its traditions impel it towards pluralism, openness, a sympathetic desire to inhabit the minds of others. There is no man, woman or child, on earth whose mind the novel cannot reconstruct. Totalitarian systems are right with regard to their narrow interests when they lock up novelists. The novel is, or can be, the ultimate expression of free speech.

I hope you’ll use your fine liberal education to preserve for future generations the beautiful and precious but also awkward, sometimes inconvenient and even offensive culture of freedom of expression we have. Take with you these celebrated words of George Washington: “If the freedom of speech is taken away then, dumb and silent, we may be led like sheep to the slaughter.”

We may be certain that Dickinson has not prepared you to be sheep. Good luck 2015 graduates in whatever you choose to do in life.

(17.05.2015)

Be the first to comment